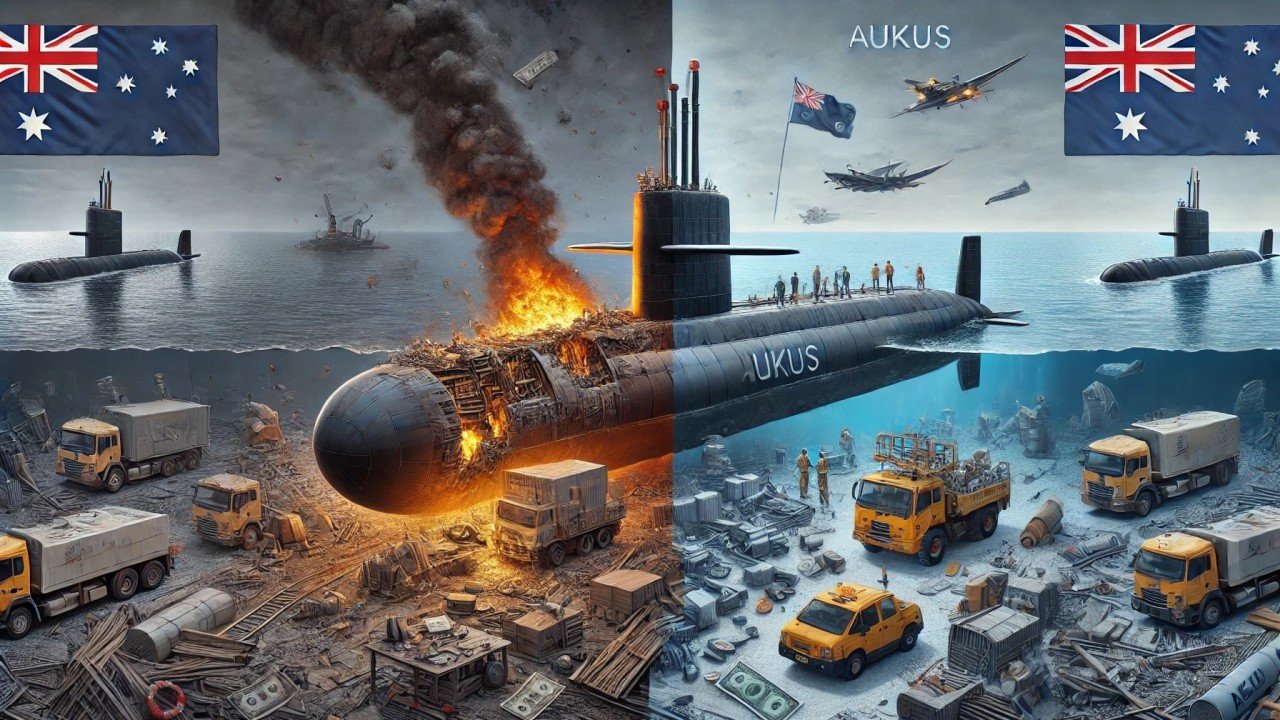

White paper: Restrictions on Nuclear Submarines in Defending Australia

Australia’s choice to acquire nuclear submarines under the AUKUS agreement raises significant strategic concerns, particularly when considering the geographical constraints and geopolitical realities of Southeast Asia. The overarching skepticism stems from the limitations of nuclear submarines in defending Australia’s critical trade routes, including oil and fuel supplies, and their operational challenges in Southeast Asian waters.

No Feasible Entry into Southeast Asia: A Strategic Deadlock

Australia’s access to Southeast Asia via nuclear submarines is severely restricted due to geographic, environmental, and political factors. The only plausible entry routes—the Torres Strait, Arafura Sea, Java Sea, and the Straits of Malacca—pose significant challenges, making a covert and strategic military presence nearly impossible. Navigating these shallow, narrow, and highly monitored waterways with nuclear submarines is not just logistically problematic but also strategically questionable.

Torres Strait: Hazardous Waters for Nuclear Submarines

Navigating the Torres Strait is fraught with risks for large nuclear submarines due to its shallow waters, averaging depths of just 7 to 15 meters. The Strait’s maze of reefs and islands poses a constant threat of grounding, making it a perilous route for submarines that need deeper waters. Additionally, the Strait’s designation as a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA) means that strict regulations are in place to protect the marine environment, further complicating military maneuvers. The need for compulsory pilotage and its status as a vital international sea lane heighten the strategic risks and undermine the feasibility of this route for nuclear-powered submarines.

Arafura Sea and Java Sea: Shallow Waters and Sovereignty Issues

The Arafura Sea, with depths mostly ranging from 50 to 80 meters, presents significant operational limitations for nuclear submarines, which require deeper waters for stealth and effective maneuverability. Similarly, the Java Sea’s average depth of just 46 meters makes it unsuitable for nuclear submarines. These areas are also within Indonesia’s 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), requiring negotiations for any military or strategic activities, making covert operations politically sensitive and strategically compromised.

Straits of Malacca: A Traffic-Choked Gauntlet

The Straits of Malacca, one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, pose another major challenge for nuclear submarines. Its shallow, narrow waters restrict operational depth and maneuverability, making stealth nearly impossible. The heavy maritime traffic and the advanced monitoring systems of bordering nations (Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore) increase the likelihood of detection, complicating any submarine operations. Moreover, international regulations under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) mandate that submarines surface and display their flag when transiting territorial waters, negating the tactical advantage of stealth.

Spratly Islands: A Strategic Hotspot but a Tactical Quagmire

The Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, contested by multiple Southeast Asian nations, have become a strategic focal point due to their rich fishing grounds and potential hydrocarbon reserves. However, the increasing militarization of this area, coupled with advanced anti-submarine warfare capabilities being developed by regional powers, makes it a highly monitored zone. While deep underwater canyons offer potential covert paths, the heavy presence of competing naval forces, including those from China, makes nuclear submarine operations highly risky and strategically untenable

Conventional Submarines: The Strategic Alternative

Given the operational constraints of nuclear submarines in Southeast Asia, conventional submarines equipped with Air-Independent Propulsion (AIP) systems, such as the @Type 214 and @Gotland-class, manufactured by @ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems and @Kockums AB present a more viable alternative. These submarines are specifically designed for operations in shallow, narrow, and highly monitored waters like those found throughout Southeast Asia. Their smaller size, quieter operation, and greater maneuverability allow them to perform crucial roles in coastal surveillance, mine-laying, and anti-ship warfare, making them far better suited for defending Australia’s trade routes and strategic interests.

Nuclear Submarines: Misaligned with Strategic Needs

The nuclear submarines’ arsenal, including ballistic and cruise missiles, torpedoes, and electronic warfare systems, is primarily designed for deep-water, strategic deterrence missions far removed from the complexities of Southeast Asian littoral warfare. The choice of these submarines does not align with the immediate defense needs of Australia, which involve protecting vital trade routes and ensuring the security of critical oil and fuel supplies. Moreover, nuclear submarines are less effective in shallow coastal waters, where their size, acoustic profile, and need for deeper operational depths make them vulnerable to detection and attack. In contrast, smaller, stealthier, and more agile conventional submarines can better exploit the complex topography of the Southeast Asian maritime environment, offering a more appropriate defense strategy for Australia’s needs.

Conclusion: Strategic Mismatch and Geopolitical Constraints

The decision to acquire nuclear submarines under the AUKUS agreement reflects a strategic misalignment with Australia’s immediate defense needs. The geographic and operational constraints of Southeast Asia render nuclear submarines ill-suited for defending Australia’s critical trade and energy supply routes. The inherent risks and limitations associated with deploying these submarines in the region highlight the need for a reassessment of Australia’s defense strategy, prioritizing platforms that can effectively navigate and operate in shallow coastal waters. Australia’s security interests would be better served by investing in conventional submarines, which offer the operational flexibility, stealth, and regional compatibility needed to safeguard its vital maritime trade routes and economic interests. This strategic pivot would not only enhance Australia’s defensive posture but also ensure that its maritime forces are better aligned with the realities of the Southeast Asian operational environment. The current approach, heavily influenced by alliance commitments rather than practical defense needs, places Australia at a strategic disadvantage in securing its maritime domain.